While sharks probably inspire the most acute fear among Sanibel Island beachgoers — mostly without good cause, by the way — jellyfish probably rank second on the list.

And, in fact, you’re statistically more likely to run afoul of one of these “sea jellies” than a big toothy marine predator.

That said, jellyfish aren’t generally a major reason to worry when you hit up the nearshore waters of lovely Sanibel, a Southwest Florida barrier isle renowned for its still-considerable natural beauty.

Let’s take a deep dive into the question: Does Sanibel Island have jellyfish?

Yes, Sanibel Island is home to many different types of jellyfish, including:

- Southern Moon jellyfish

- Cannonball jellyfish

- Sea nettles

- Upside-down jellyfish

- Sea wasps

- Portuguese man-o’-war (which is not technically a jelly!)

Severe jellyfish stings, however, are rare in Sanibel Island, especially if you follow basic precautions.

Let’s take a look at each of these jellyfish, photos and ways to identify them, plus sting history and jellyfish season at Sanibel Island. Along the way, hopefully you’ll gain a greater knowledge and appreciation of these gorgeous animals!

Types of Jellyfish at Sanibel Island, FL

From the estuarine flats of the sounds and back bays to the pelagic waters of the Gulf of Mexico, a variety of sea jellies call Sanibel Island’s greater neck of the woods home.

The Sunshine State, after all, plays host to more than a dozen species of jellyfish, and most of these could conceivably be chanced upon somewhere in Sanibel’s general radius at one time of year or another.

That said, we’ll just be homing in on a relatively few important species: several of the most commonly encountered kinds of jellyfish, plus a very rarely seen but potentially pretty dangerous species and a similarly risky sea-jelly lookalike.

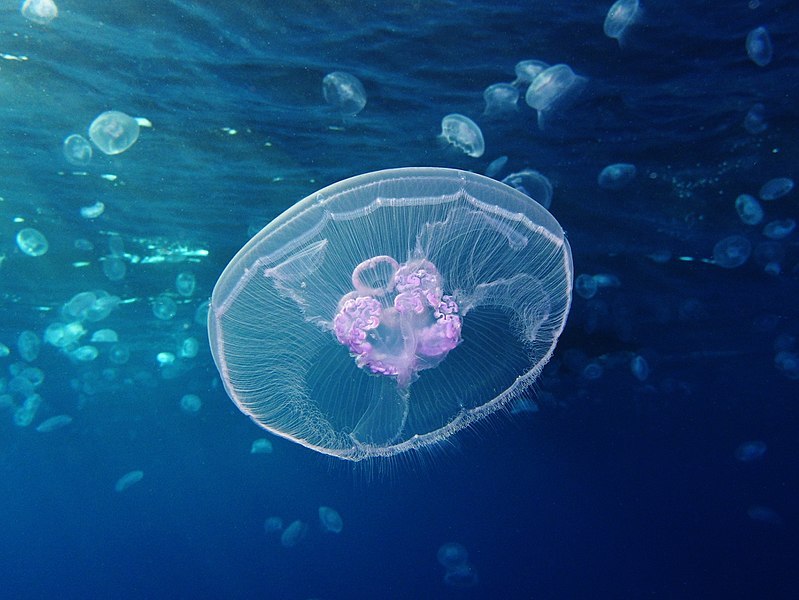

Southern Moon Jellyfish

This is the jellyfish you’re most likely to see in Sanibel waters or washed up on the beaches. It’s quite an easily identifiable critter, too, what with the horseshoe pattern dominating its bell.

These jellies do bear stinging cells, but typically produce an exceptionally minor aggravation on contact: often merely a slight prickly feeling.

(Some people may have more painful reactions, but still nothing particularly to write home about.)

Their dense, fine tentacles are very short, to boot.

Cannonball Jellyfish

This distinctive jellyfish is also often called the “cabbagehead,” both names aptly describing the creature’s large, round bell — pale with a brownish, reddish, or purplish band around the base — which also gives it something of a mushroom look.

(The somewhat larger mushroom cap jellyfish, also native to the Gulf of Mexico, resembles the cabbagehead but lacks that brownish band at the base of the bell.)

A stubby cluster of oral arms hangs tightly below that hulking bell.

Cannonball jellies are quite numerous, especially in late summer and early fall, but fortunately they don’t pack much of a punch at all in terms of their sting; they’re more notorious for mucking up fishing nets.

Sea Nettle (Atlantic Bay Nettle)

A major academic study in 2017 suggested the sea nettles (genus Chrysaora) of the eastern U.S. coasts are not one single species as commonly believed, but actually two: the Atlantic sea nettle and the Atlantic bay nettle.

That research indicated that the latter, restricted to estuaries on the Atlantic coast, is the primary sea nettle of the Gulf of Mexico, where it’s not only bound to estuarine waters but also occupies pelagic habitat.

Suffice it to say that the sea nettle (as we’ll just generally refer to these local Chrysaora jellies) is both one of the area’s loveliest jellyfish and arguably the all-around peskiest.

The sea nettle is characterized by a vividly colored brownish, reddish, or orangeish bell and a long, elegant train of oral arms and trailing tentacles.

Gorgeous to look at, but not something you want to tangle with: The nettle’s dangles come armed with some pretty darn stiff stinging cells.

Sea nettles aren’t exceptionally dangerous jellyfish, but the stings are definitely unpleasant, and severe responses may linger awhile.

Upside-Down Jellyfish

The seafloor in Sanibel Island’s general vicinity plays host to the unique upside-down jellyfish (Cassiopea), named for its habit of lying bell-down, tentacles-up amid seagrass or silty beds.

The posture is all about their lifestyle: Its rather fancy-looking underparts include symbiotic microorganisms, dinoflagellates, which through their photosynthetic activity produce food for the jellyfish.

Hence Cassiopea’s topsy-turvy routine, which better exposes its tiny and exceedingly helpful tenants to the sunlight that powers photosynthesis.

Interestingly, recent research has confirmed that upside-down jellies also release mucus particles charged with stinging cells.

These “cassiosomes,” as they’re called, are responsible for the so-called “stinging water” you may encounter if you swim or snorkel in the general vicinity of upside-down jellyfish. (Nothing particularly severe, mind you.)

The thought is that Cassiopea releases those cassiosomes for the purpose of supplementing its mostly photosynthetic diet with tiny live prey such as zooplankton.

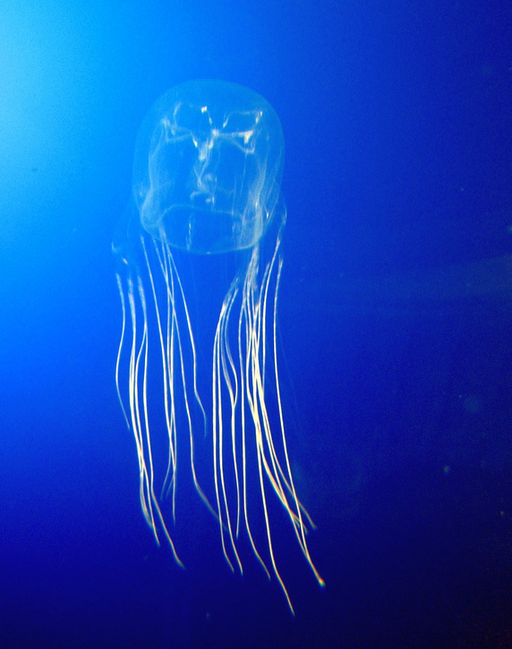

Sea Wasp

The most dangerous jellyfish you could realistically encounter in the waters around Sanibel Island—though the odds would be quite low—is the sea wasp.

This is a widely used generic name for the notorious box jellyfish, or cubozoans, a related but distinct class to the “true” jellyfish, or scyphozoans.

They’re quite easy to recognize, given their clear, squared-off bells with relatively few, relatively thick tentacles clustered at the corners.

Certain species of sea wasp from the Indo-Pacific region possess extremely potent, commonly fatal venom, and are responsible for numerous deaths in places such as Australia and the Philippines every year.

Fortunately, the sea wasps periodically reported from Florida waters aren’t so fearsomely venomous, though their stings can be exceedingly painful and may require medical treatment.

While the four-handed box jellyfish is the main sea wasp on the Atlantic coast, the mangrove box jellyfish, primarily a Caribbean species, appears to be more prevalent (though rare) in the Gulf of Mexico.

Other Sanibel Island Jellyfish & Sea-Jelly Lookalikes

Among the most newly described jellyfish species that call the Gulf of Mexico home: the pink meanie, first identified around the turn of this century when it was observed feeding on one of the epic blooms of moon jellies that often occur in the Gulf.

This is an impressive jellyfish, with a bell that may be several feet across and tentacles that can exceed 70 feet in length—and then there’s that pink hue! You’re not terribly likely to see a pink meanie close to Sanibel, but it’s possible.

The same goes for the lion’s mane, which in more northerly latitudes can attain enormous size—it’s the world’s biggest jellyfish—but tends to be much smaller in Florida waters.

This is a cold-water jellyfish and the Gulf of Mexico, where it has been reported, is on the margins of its preferred range.

Meanwhile, one of the highest-profile organisms in Florida that folks often refer to as a jellyfish is actually not technically (depending on your definition) a sea jelly, per se.

The Portuguese man-o’-war, while manifesting a jellyfish-like medusa form, is actually a colonial “siphonophore” composed of many individual organisms, zooids, living together as one.

For all intents and purposes, though, it might as well be a jellyfish.

Drifting about with the wind and currents thanks to its strikingly purplish or blueish buoyant, sail-crested float (or pneumatophore), the Portuguese man-o’-war can cover long oceanic distances, and sometimes shows up well north of its usual tropical and subtropical haunts.

It may wash ashore in large numbers as well. Its tentacles can extend dozens of feet below the pneumatophore and deliver a very nasty (though usually not life-threatening) sting; the sheer length of the tentacles makes getting tangled in a Portuguese man-o’-war dangerous on account of how many stinging cells you could come in contact with.

Jellyfish Season & Sting History at Sanibel Island

While jellyfish of one kind or another might conceivably be seen off Sanibel Island any time of year, “jellyfish season” would mainly be considered the summer and fall.

That’s partly a reflection of seasonal abundance of sea jellies, which often “bloom” in late summer and early fall in response to warmer water and population spikes in the zooplankton they prey on.

It’s also because that’s when more people are likely to actually be in the water, exposed to “stingers.”

Nonetheless, the chances you’ll be stung aren’t especially high, especially if you use common sense.

And by far the vast majority of stings in local waters are going to be mild, with very temporary and localized effects.

The most serious situations would involve somebody getting a large number of stings—as could happen if you somehow find yourself snarled in the long tentacles of a Portuguese man-o’-war, or drifting into a whole mess of jellies—or experiencing an allergic reaction to a sting.

That’s especially true if the person having the allergic response is alone, or swimming offshore (where drowning becomes a grave concern).

Keep in mind that more than a few jellyfish injuries occur not in the water but on the beach, when people step on or prod washed-ashore jellies still very much capable of stinging.

Indeed, the stinging cells of a beached jelly or Portuguese man-o’-war can remain active even after the organism itself has expired.

While due to their local abundance you’re probably more likely to get stung by a moon jelly — not a big deal — the most frequent serious stings in Southwest Florida likely derive from the sea nettle and perhaps the Portuguese man-o’-war.

Box jellies would be a rare concern, but given their nearly transparent form they can be trickier to see in the water than most other local sea jellies, which can lead to inadvertent run-ins, and a sea-wasp sting is more likely to warrant medical treatment.

Avoiding Jellyfish Stings at Sanibel Island (Tips & Things to Know)

Heed any posted warnings about jellyfish — for example, the purple beach flags that indicate hazardous marine life along a particular beachfront. Sanibel Island doesn’t have regularly lifeguarded beaches, so you can’t count on up-to-date advisories on arrival.

Sustained onshore winds or currents will drive sea jellies into exposed coastlines, so be especially watchful when you take a dip under these conditions.

Jellyfish—or bits of disintegrated jellyfish, which can still potentially sting you—are often found among large accumulations of flotsam in the water.

It goes without saying (we hope) that if you visit a beach with plentiful washed-up jellies, you might expect a fair amount in the nearshore surf.

Be careful going swimming near lots of beached jellies, or choose a different time or place to do so. As we’ve already alluded to, you should avoid touching beached sea jellies with bare feet or fingers.

Your average jellyfish sting incurred on Sanibel Island will be mild. That said, you always want to be mindful of potential allergic reactions, which can make even a relatively harmless jelly’s sting a serious matter.

Call 911 or the toll-free national Poison Help Hotline at 1-800-222-1222 if you or somebody else is having an allergic or otherwise serious reaction to a jellyfish sting.

Sanibel Internal Medicine (2495 Palm Ridge Road, Sanibel, FL; phone: 239-395-2005) offers a walk-in clinic and advertises the treatment of jellyfish stings among the services it provides.

Applying household vinegar to the site of a jellyfish sting is a widely used method to neutralize stinging cells left on the skin. (Many Florida lifeguard stations come equipped with vinegar for this purpose.)

Just to clear up a persistent rumor: Despite what you may have heard (or seen in movies), urine isn’t an effective topical treatment!

Soaking stung skin in hot water for a half-hour or so can help mitigate irritation; cortisone cream and/or antihistamines are an option for relieving lingering pain and itching.

Wrapping Up

A visit to Sanibel Island definitely doesn’t need to be sabotaged by constant fear of jellyfish.

General awareness of your surroundings, both on the beach and in the water, goes a long way toward keeping you clear of those stinging oral arms and tentacles.

And if you do happen to find a jellyfish washed ashore on the sand, or drifting just below the surface alongside a pier, take a moment to marvel at its delicate splendor—and at the fact that these silent, gelatinous drifters have been doing their thing in the world’s ocean for several hundred millions of years!

For more beach guides, check out:

Hope this helps!