Fort Lauderdale is one of the bustling anchors of southeastern Florida’s Gold Coast and the Greater Miami area.

That—and, of course, the tropically tinted climate that defines this part of the Sunshine State—makes it a top-draw destination for vacationers and “snowbirds.”

Many Fort Lauderdale-area visitors, naturally, are keen to get into (and on) the warm, generally friendly Atlantic as well as the Intracoastal Waterway. Beachgoers enjoy swimming, watersports, and surf-casting, while paddlers and boaters might well be sampling the world-class sportfishing from inshore estuaries and canals to the bluewater realm out to sea.

That puts quite a lot of folks in potentially close proximity to sharks, which are numerous and diverse here in what’s variously classified as part of the South Florida/Bahamian Atlantic or simply South Florida Coastal marine ecoregion.

These include offshore pelagics as well as sharks haunting seagrass beds, mangrove ecosystems, and the coral gardens that, in Fort Lauderdale’s waters, form the northeastern edge of South Florida’s extensive reef system.

So if you’re planning a trip, or even if you’re a local, let’s break it down:

Are there sharks in Fort Lauderdale, Florida? How common are shark attacks in Ft. Lauderdale?

Some of the most common types of sharks found off of Ft. Lauderdale include:

- Blacktip sharks

- Spinner sharks

- Sandbar sharks

- Dusky sharks

- Blacknose sharks

- Lemon sharks

- Bull sharks

- Tiger sharks

- Great hammerhead sharks

- Bonnethead sharks

- Nurse sharks

- Great white sharks

- Sand tiger sharks

- And even more!

But have no fear! While Florida sees a relatively large number of shark attacks compared to other U.S. states, shark encounters are still quite rare. Fort Lauderdale itself has only confirmed about 16 unprovoked shark attacks since records began being kept.

Let’s learn more about the types of sharks in Ft. Lauderdale, photos, stats, shark attack incidents, and more!

Types of Sharks Off Fort Lauderdale

The Fort Lauderdale area, and indeed the whole southeastern coast of the U.S., supports a globally significant and impressively varied stock of sharks.

The following list by no means covers them all, but does include many of the species visitors here are either most likely to see or most concerned about.

Blacktip Shark

Blacktips are members of the shark family Carcharhinidae: the so-called “requiem sharks” that serve as some of the ocean’s most important top-level predators, and include many of the larger shark species.

Blacktip sharks aren’t actually all that large, generally reaching about five or six feet.

They’re very common along the eastern coast of Florida, including in Fort Lauderdale’s backyard, and are frequently seen hunting schooling fish close to shore.

Spinner Shark

Similar in size and appearance to blacktips, spinners can be distinguished by their black-marked anal fin and a dorsal fin positioned farther back.

Spinner sharks are named for their habit of leaping—sometimes corkscrewing—out of the water as they chase baitfish into shallow waters: a pretty darn awesome sight if you happen to catch it while sunbathing or shelling on an area beach.

(Blacktips will breach as well, though, so it can be tough to tell which flashy little requiem shark you saw going airborne.)

Sandbar Shark

Averaging larger than blacktips or spinners, sandbar sharks (also rather boringly called “brown sharks”) are important coastal predators pretty easily keyed out by their dramatically tall first dorsal fin.

These sharks—found year-round off Florida with northerly populations also migrating into Sunshine State waters for the winter—commonly hunt near the bottom, snatching rays, eels, smaller sharks, and other varied prey.

Dusky Shark

The dusky shark—a wide-ranging tropical and temperate requiem species, and known in other parts of the world by various alternate names, including black whaler—is a good-sized hunter that maxes out around 14 feet long.

Not frequently encountered in local waters, duskies nonetheless are found off the Fort Lauderdale coast, ranging from inshore shallows to the offshore continental shelf.

These apex predators are notably migratory, moving north in summer and south in winter.

Blacknose Shark

The little blacknose shark, which rarely reaches much more than four feet long, is named for the dark splotch on the tip of its snout, more noticeable in juveniles.

Blacknose sharks hunt small fish, octopuses, and squid over sandy flats and reefs, and do their best to steer clear of the numerous larger sharks that target them as prey.

Lemon Shark

Among those bigger relatives that might snatch a blacknose is the lemon shark, one of the most significant inshore and nearshore predators along the South Florida coast.

Possessing a vaguely flattened body shape, with first and second dorsal fins of nearly the same size, lemon sharks prowl seagrass pastures, reefs, sandbars, and mangrove shallows, which also serve as important nurseries.

Reaching about 11 feet or so, lemon sharks prey not only on smaller sharks but also rays, crabs, and just about anything else they can get their robust jaws around. Some evidence suggests they may occasionally hunt cooperatively.

Bull Shark

The bull shark is probably the most all-around notorious of Fort Lauderdale’s regularly seen sharks.

This stocky requiem species, which exceptionally may reach 13 feet long, is on the pugnacious side of things, commonly enters estuaries, canals (including in the Fort Lauderdale suburb of Lighthouse Point), and even freshwater river reaches, and boasts heavy, powerful jaws.

Bull sharks hunt everything from crustaceans and fish to seabirds and dolphins, and are ranked among the most potentially dangerous sharks.

Tiger Shark

This magnificent beast—named for the body striping that fades with age—is the biggest of all requiem sharks, known to reach the better part of 20 feet long and more than a ton in weight.

Besides the pattern of its hide, the tiger shark is distinguished by its blocky-looking head and broad jaws, studded with asymmetrical serrated teeth.

Resting at the top of the food chain in coastal waters, tiger sharks are famed for their indiscriminate diet: They’ll chomp rays and smaller sharks, crabs and spiny lobsters, gulls and pelicans, and animals as hefty as sea turtles, bottlenose dolphins, and likely the odd manatee.

They’re also known for occasional attacks on humans, though—like the bull shark and other potentially dangerous species—they mostly steer clear of us.

Great Hammerhead Shark

Several medium- to large-sized species of hammerhead shark could conceivably be seen in Fort Lauderdale’s waters, but the biggest of all—and not all that uncommon—is the great hammerhead.

This grand predator, which cruises nearshore waters after stingrays and other prey, may reach on the order of 21 feet long, though most are in the 10- to 15-foot range.

Anglers prize great hammerheads for their fighting spirit, but the stress of such encounters—legal as a catch-and-release recreational sport—can sometimes have tragic consequences for the animals.

In April 2022, for instance, an 11-foot-long female great hammerhead—who was unfortunately pregnant, bearing a slew of unborn pups—washed ashore north of Fort Lauderdale on Pompano Beach with a hook in her jaws, suggesting she may have died from the effects of being caught.

Bonnethead

At the other end of the hammerhead size scale, the bonnethead is a pintsized shark often three to five feet or so long.

Fond of crabs (and even nibbling seagrass, in the only as-of-yet documented shark species to engage in plant-eating), bonnetheads are common sights in coastal shallows, bays, and estuaries, and are often caught by surf-casters. They migrate into deeper waters as well as southward during winter, as they’re intolerant of cold.

Nurse Shark

Nurse sharks are good-sized members of the carpet-shark order, sporting distinctive barbels around their small mouths and a strikingly long upper tail (caudal) fin.

Occasionally growing as large as 14 feet, these often-sluggish sharks are sometimes seen by divers and snorkelers resting on sandy seafloors or amid reefs.

(Sluggish, yes, and eaters of small fish and crustaceans, but nurse sharks will understandably defend themselves if, as sometimes happens, irresponsible divers tug at their fins or otherwise crowd them.)

Great White Shark

It’s worth mentioning the great white shark, because recent tracking studies and observations confirm this mighty creature—the biggest predatory fish in the sea, known to reach or exceed 20 feet and weigh more than two tons—frequents Florida waters more regularly than previously understood, especially in winter.

That said, your average visitor to the Fort Lauderdale seashore is almost assuredly not going to see this most infamous of all sharks, which in these parts generally favors more offshore waters.

Great whites are the largest members of the shark order Lamniformes, also called the mackerel sharks.

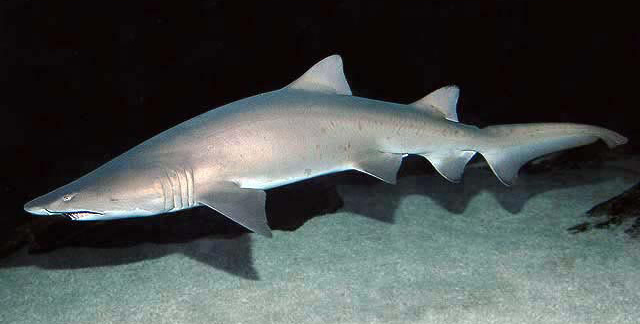

Sand Tiger Shark

The sand tiger—not at all related to the true tiger shark, and indeed a distant lamniform cousin of the white shark—must rank among the most familiar of sharks, on account of how common it is in aquariums and oceanariums.

Easy to keep in captivity, it also presents a pretty striking appearance, namely on account of a mouthful of sinister-looking snaggleteeth. That toothy front end makes the sand tiger unmistakable, but it’s also known for first and second dorsal fins of essentially the same size, and the well-set-back first dorsal.

In the waters off southeast Florida, it’s occasionally seen by divers exploring reefs, where the sand tiger drifts about sluggishly but can bolt into action to grab the small fish it favors.

Swimmers or paddlers, however, are unlikely to encounter this impressive but mostly harmless shark.

Other Sharks

A few other mackerel sharks can be found in the pelagic wilds usually well off the Gold Coast of Florida: threshers, with their ridiculously long upper tail fins, and shortfin and longfin makos, renowned for their speed and leaping ability.

A number of other requiem sharks might possibly be spotted in regional waters, too: from the bronze whaler to the formerly common, now majorly reduced oceanic whitetip.

The much more diminutive Atlantic sharpnose shark is also in the requiem family, and one of a number of little sharks—including various dogfishes—native to this coastal zone.

Shark Attack History & Statistics in Fort Lauderdale

Florida sees by far the most shark attacks in the U.S., which in turn leads the world on this count.

The Sunshine State has seen 900-odd unprovoked shark attacks since 1837, according to the (Florida-based) International Shark Attack File (ISAF).

But given the staggering number of people soaking and swimming in Florida waters every year, it’s clear the odds of being bitten by a shark here are still very low.

And emphasis on “bitten”: Most shark “attacks” in Florida are better described as sharkbites or even shark nips, as the main species responsible—the blacktip—is a small creature thought to periodically bite feet, hands, or legs out of confusion when targeting baitfish.

Compared with some nearby regions of Florida, the Fort Lauderdale area hasn’t seen all that many shark attacks, and indeed the ISAF records only 16 unprovoked ones in Broward County since 1882.

No fatal attacks are known from Broward. Florida’s leading counties for shark attacks, for reference, are Volusia (337), Brevard (155), and Palm Beach (81).

The relatively few sharkbites that have occurred around Fort Lauderdale have tended to be pretty minor. A surfer in 2015 off Deerfield Beach was bitten on the foot by an estimated five-foot-long spinner shark. A small shark bit the leg of a 22-year-old woman tubing in the Intracoastal Waterway in Fort Lauderdale.

In September 2007, two minor bites were recorded in the area: A Fort Lauderdale swimmer received a small bite from what might have been a spinner, while a snorkeler off Lauderdale-by-the-Sea had a nurse shark bite his abdomen. Going back further, a roughly eight-foot-long great hammerhead nipped the toe of a spearfisher in Fort Lauderdale in July 2003.

Among reasonably common and regularly seen species, the sharks most capable of delivering serious injury to a human being in the Fort Lauderdale area would generally be the great hammerhead (toe nibbles notwithstanding), the bull shark, and the tiger shark; bulls and tigers have been responsible for most of the serious—and, very rarely, fatal—attacks on people in Florida.

But, again, such events—low-odds enough to begin with—have just not been logged much in the vicinity.

Wrapping Up

All sorts of common-sense safety practices—including avoiding swimming at dusk or at night, avoiding swimming alone, trying to steer clear of schools of baitfish as well as active fishing operations, and taking off shiny jewelry before getting in the water—can further reduce the already low probability you’ll run into the business end of a shark on a Fort Lauderdale visit.

Remember, sharks are essential members of the ocean ecosystem and have vastly more to fear from humankind than the other way around.

Most Fort Lauderdale vacations won’t include a sighting of a shark, and those that do—a spinner spiraling out of the water off the beach, say, or maybe a little bonnethead or blacktip cruising off a pier—will be all the more memorable for it.

For more Florida shark guides, read:

Hope this helps!