Sitting pretty on the Pacific about halfway between Los Angeles and San Diego, Laguna Beach is one of the legendary destinations along the Southern California coast.

Its backdrop of the San Joaquin Hills, its inviting sands—and, naturally, that balmy, sun-kissed climate—draw visitors from the world over.

A lot of those visitors want to get in the water, at least in summertime. And those beachgoers looking to soak or surf might find thoughts of hazardous marine life crossing their mind.

Around these parts, that means thoughts of sharks, stingrays, and—yes—those gelatinous floaters we know as jellyfish or sea jellies.

Does Laguna Beach, CA have jellyfish?

Laguna Beach is home to many types of jellyfish. A few of the most common species of jellies you’ll find in this area are:

- Pacific sea nettles

- Black sea nettles

- Purple striped jellyfish

- Moon jellyfish

- And fried egg jellyfish

Laguna Beach is not a particularly dangerous area for jellyfish stings. Encounters with the moon jelly are most common, but their stings are extraordinarily mild. Running into the more dangerous sea nettles does happen on occasion, but it’s rare in this area.

In this article, we’ll introduce you to common species of Laguna Beach jellyfish, discuss jellyfish stings in the area, and run through some of the basics of jellyfish safety.

Types of Jellyfish in Laguna Beach, CA

The productive waters of the Southern California Bight support a rich array of sealife, large and small, and that marine roster includes quite a few sea jellies.

(It also includes a fair number of jellyfish lookalikes, such as comb jellies and, occasionally, by-the-wind sailors.)

Here are some of the more frequently seen species of true jellyfish.

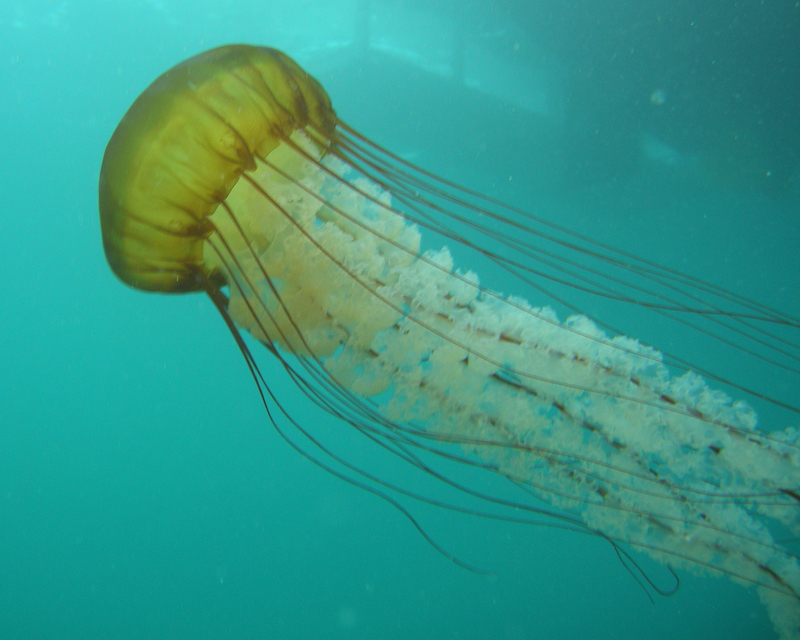

The Pacific Sea Nettle

This legitimately gorgeous jellyfish, also known as the West Coast sea nettle, boasts a reddish-golden bell that may be 18 inches across and an ornate train of tentacles and oral arms (or “mouth-arms”) that can span up to 15 feet long.

The stinging cells (or nematocysts) of those tentacles and oral arms paralyze fish larvae, zooplankton, smaller jellies, and other little prey.

For humans, though, the sharpish sting of the Pacific sea nettle is not usually dangerous.

Covering as much as 3,600 vertical feet in their daily movements up and down the water column, Pacific sea nettles typically increase in population in late summer in response to water temperature and planktonic blooms.

Armed (mildly) as it is, the Pacific sea nettle is nonetheless munched on by a lot of other sea creatures. Among the most noteworthy is the leatherback turtle, by a fair amount the biggest of all the sea turtles; it may approach a ton in weight. The leatherback’s diet is dominated by sea nettles.

Leatherbacks show up off the California coast in the summer, when they snack heavily on Pacific sea nettles as well as most of the jellyfish species we’re profiling here.

The Black Sea Nettle

This striking-looking relative of the Pacific sea nettle was only fully described and named in 1997 (though it had been photographed decades before).

In fact, the black sea nettle was the heftiest invertebrate discovered in the 20th century. And hefty it is, with a dark-purple bell that may span more than three feet in diameter, oral arms that can reach 20 feet, and tentacles that may be longer yet.

Black sea nettles occasionally show up conspicuously off Laguna Beach and other Southern California beaches, as in July of 2013, when quite a few swimmers ended up stung by these mysterious jellies.

These appearances are thought to align with periods of warmer local waters, as in El Nino years. Fortunately, as with the Pacific sea nettle, the sting of the black sea nettle, while definitely unpleasant, isn’t life-threatening.

The Purple Striped Jellyfish

A relative of the Pacific and black sea nettles, the purple striped jellyfish ranges from Washington to Southern California, and it’s particularly abundant in the southern part of its range.

Mature individuals have a good-sized bell that may be two or three across and comes patterned by radiating purple stripes.

These guys pack quite a potent sting, though it’s normally not dangerous.

According to the Scripps Institute of Oceanography, purple striped jellies are found year-round off the Southern California coast, but rarely show up in large blooms like some of the other local kinds.

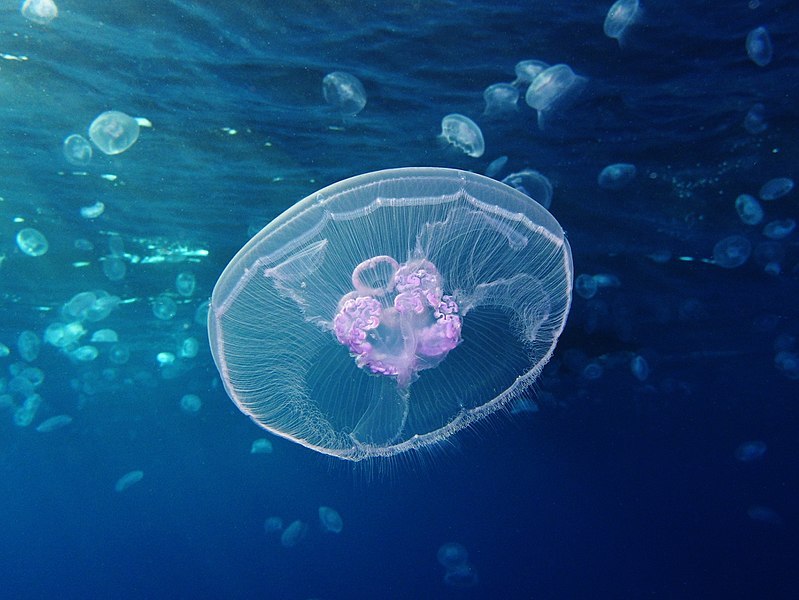

The Moon Jelly

The moon jelly, by contrast, is known for its frequent and prolific blooms, especially in late winter through spring.

This very common and familiar jellyfish is unmistakable with its clear, horseshoe-patterned bell, and lacks the impressive draping tentacles and oral arms of the species we’ve covered so far.

Its tentacles, by contrast, are very stubby and fine, tightly ringing the bell and barely visible.

The moon jelly’s sting is extremely minor, if it’s felt at all.

For the most part, our skin’s too thick—and its stinging cells too paltry—to make for even much irritation on contact.

The Fried Egg Jellyfish

Another rather extraordinary-looking creature (though, let’s face it, sea jellies as a rule are pretty darn extraordinary-looking), the fried egg jellyfish has a translucent bell cored by a yellow, yolk-like gonad. (Indeed, another name for this species is the egg-yolk jelly.)

This is, along with the black sea nettle, one of the largest of the common local jellyfish, with tentacles that may stretch 20 feet.

The fried egg jellyfish often hovers, basically stationary, in the water column, waiting for other sea jellies—among its primary prey—to drift into its dense and long tentacle draperies.

Its stinging cells are good at dispatching other jellyfish, but don’t impart a particularly strong sting when it comes to people.

Laguna Beach Jellyfish Stings (How Common, Season & More)

On the whole, Southern California is not any kind of major hotspot for jellyfish stings.

The most commonly encountered species, as we’ve discussed, tend to deliver mild to moderately painful, but not life-threatening, stings.

Truly dangerous species, such as the sea wasps or box jellies, are uncommon here.

Stings are most likely when blooms of jellyfish drift inshore. Masses of moon jellies, while periodically seen in coves and harbors, aren’t usually much of a problem in the stinging department.

But the large numbers of sea nettles that occasionally occur close to shore may result in beachgoers getting stung.

As we’ve mentioned, black sea nettles showed up around Laguna Beach in the summer of 2013; quite a few folks were stung by these otherwise rarely seen jellies—though not seriously—at Thousand Steps Beach over the Fourth of July weekend.

Avoiding Jellyfish Stings at Laguna Beach (Tips & Things to Know)

As we’ve made clear, jellyfish aren’t a particular cause for concern at Laguna Beach, though anytime you get in the ocean there’s a chance you might brush against one.

Surfers or divers in wetsuits are pretty well protected from the stings that most common Southern California jellyfish might deliver, aside from the small areas of bare flesh.

Swimmers are more exposed, unsurprisingly.

If you see a bunch of jellyfish washed up on the beach, you might think twice about getting into the water.

That’s sort of common-sense level, as a bunch of sea-jelly beachwrack suggests a localized bloom and inshore currents likely full of the critters.

Be aware that jellyfish—or bits of broken-apart jellyfish, which still can sting—may be floating amid dense areas of flotsam.

Generally speaking, sea jellies sometimes accumulate where waves or currents lose steam, in eddies around pilings and the like, or anywhere there’s slackwater.

Though beached moon jellies might not pose much of an issue, you should avoid touching other species of jellyfish you see washed up on the beach.

Some of these stranded sea jellies may still be alive, but even after they’ve expired their stinging cells remain active for awhile—even weeks.

Vinegar is an effective topical treatment for most jellyfish stings, and for that reason is often part of the arsenal of lifeguards.

(Don’t fall for that old wives’ tale about using urine to stop the stinging—partly because it’s pretty gross, and partly because it doesn’t work.)

The most serious stings around these parts would be those inducing an allergic reaction, so watch for signs of such a response and seek medical attention in that event.

An allergic reaction to a jellyfish sting, which could expose an offshore swimmer to real trouble (not least from drowning), is another reason why you should always use the buddy system when getting in the ocean.

Wrapping Up

Jellyfish aren’t something to lose sleep over for the most part—not in southern California, anyhow.

These are fascinating invertebrates that have stuck around in the world’s oceans for hundreds of millions of years, proving their evolutionary mettle and forming important low-level rungs in the marine food web.

They aren’t out actively looking for swimmers and surfers to sting, and the most frequently seen Laguna Beach-area species pose far less danger than the box jellies of tropical and subtropical waters.

For more guides, check out:

Hope this helps!