Tybee Island, Georgia is a super-popular seaside playground, offering extensive beachfront and friendly waters just a stone’s throw from Savannah.

But it’s not all benign sand and surf: Tybee beachgoers need to be cognizant of potentially harmful marine life, even though the overall risk of any serious bites or stings is relatively low.

Let’s tackle the question on everyone’s mind:

Does Tybee Island have jellyfish?

Yes, jellyfish come with the territory as far as the waters off Tybee Island are concerned, but they’re typically not dangerous — beyond an unpleasant sting. Most species are essentially harmless to people, none could ever be termed aggressive, and a little common sense and awareness can go a long way toward avoiding stings from more potent “sea jellies.”

Types of jellyfish common near Tybee Island include:

- Cannonball jellyfish

- Lion’s mane jellyfish

- Southern Moon jellyfish

- Sea or Bay Nettles

- Mushroom cap jellyfish

- And more

These marine invertebrates—supremely simple and supremely successful creatures that have been around for hundreds of millions of years—belong to a diverse and widespread group called the cnidarians, and include the “true jellyfish” of Class Scyphozoa and the box jellyfish of Class Cubozoa.

Other cnidarians, including hydrozoans such as by-the-wind sailors, are informally called jellyfish, and we’ll touch on a few of these sea-jelly relatives in this article.

Read on to learn about what kinds of jellyfish call the coastal and estuarine Atlantic waters of Tybee Island home, and how you can stay safe around them!

Types of Jellyfish at Tybee Island, GA

The following is not a completely comprehensive list of the jellyfish potentially found in Tybee Island’s nearshore waters, but it covers the most commonly seen or otherwise notable.

Cannonball Jellyfish

Also known as the cabbagehead jellyfish—or simply the “jellyball”—this is likely the most common of the true jellyfish in Georgia’s coastal waters.

A burly-looking creature, the cannonball jelly lacks long tentacles; stubby oral arms protrude below the big bell, which as the common names suggest is strikingly round.

While the species has a toxic mucus it employs in defense, it doesn’t produce a severe sting, and thus poses very little threat to human beings.

Though notorious for fowling nets and otherwise disrupting some fishing operations, cannonballs actually support their own sturdy commercial fishery, as the species is considered a delicacy in some Asian cuisines.

Interestingly, among various other species of sealife that may shadow or even shelter among cannonball jellyfish, spider crabs often hitch rides within the cannonball’s bell.

A potentially year-round jellyfish in Tybee Island’s waters but most common from spring through fall, cannonballs often wash ashore in great numbers on the heels of onshore winds and high tides.

Mushroom Cap Jellyfish

The mushroom cap jelly (sometimes just called the mushroom jelly) is a bit of a cannonball lookalike, but grows a fair bit larger than that more numerous species—it may span 20 inches across—and has a flatter and softer bell.

It’s more common off Georgia in winter.

Its sting— resulting from stinging cells, aka nematocysts, located in the bell (the mushroom jelly, like the cannonball lacks tentacles) —is exceedingly mild.

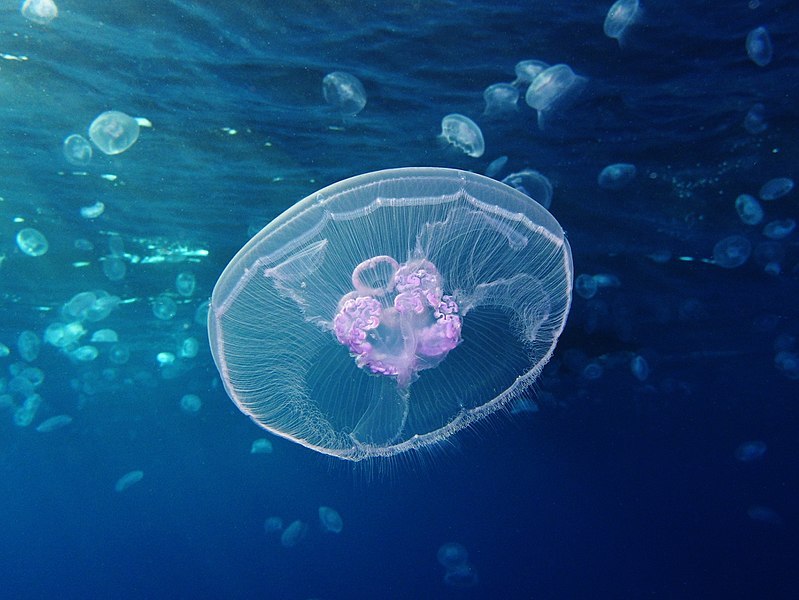

Southern Moon Jellyfish

The moon jelly is another very familiar jellyfish easily recognized by the four pinkish, horseshoe-shaped glands ringing the center of its transparent bell (which may grow as large across as a typical dinner plate).

A summertime visitor to Tybee Island waters, moon jellies have short tentacles that produce only a very mild sting.

Sea/Bay Nettles

Long lumped together as one species, Atlantic sea nettles and Atlantic bay nettles have recently been separated out as their own distinct types of sea nettle (Chrysaora): the former more of an oceanic species, the latter an estuarine inhabitant of inshore waters.

(Parsing out which is which is basically a moot point for your average beach lover, however.)

These are some of the loveliest of Georgia’s jellyfish, characterized by reddish or brownish bells undergirded by ornate draperies of oral arms and tentacles.

Those tentacles can pack a bit of a punch—hence the whole “nettle” part of these jellies’ names.

While not exceptionally severe except in the case of allergic reaction, the stings of sea and bay nettles can be quite painful and take some time to fully heal.

As with many of the jellies on the list, sea and bay nettles are most abundant around Tybee Island in the summer.

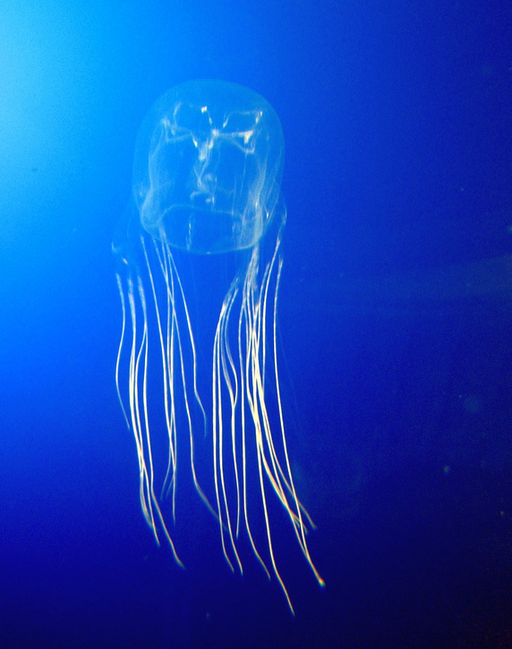

Sea Wasp or Box Jellyfish

The most dangerous of Tybee Island jellyfish, the sea wasp is a cubozoan: that is, a representative of the infamous class of cnidarians also commonly called box jellyfish.

That name reflects their cube-like bell, with tentacle bunches extending from each of the corners.

The main local sea wasp is the four-handed box jellyfish, widespread off the U.S. Southeast coast.

Generally speaking, this sea wasp isn’t so fearsomely potent as the box jellies that swimmers and board-riders fear in the waters of Australia and elsewhere in Oceania.

But no question the four-handed box jellyfish’s stings can be severe and painful, and could even be life-threatening to small children.

Part of the issue with the sea wasp is its transparency: Its clear bell can make it difficult to discern in the often murky-ish depths off Tybee Island.

This primarily subtropical jelly is mainly a mid- or high-summer phenomenon in the area.

Lion’s Mane Jellyfish

The magnificent lion’s mane is the biggest of all jellyfish:

In exceptional cases, its tentacles—which can number in the thousands, divided into eight clusters, and give the jelly its name—may exceed 100 feet in length, and large specimens may boast a lobed bell six feet or more across.

This impressive beastie is also sometimes called the “winter jellyfish,” a reflection of its cold-water preferences; the winter months are definitely when it’s most likely to be seen around Tybee Island.

While the lion’s mane—which feeds on a variety of prey, including other jellies—has a stiff sting, your average Tybee Island swimmer is unlikely to run into one given the species’ seasonality.

Lion’s-mane stings tend to be rated a bit harsher than those of the moon jelly, but aren’t usually dangerous.

Jellyfish-like Creatures

A variety of other marine invertebrates superficially resembling true jellyfish and box jellies may conceivably be encountered in the waters off Tybee Island, include various harmless “comb jellies,” gelatinous creatures propelled by cilia, such as the sea gooseberry and the pink comb jelly.

But the best-known of the “pseudo-jellyfish” is the Portuguese man-o’-war, which is technically a siphonophore: an organism composed of a colonial assemblage of clonal constituents called zooids.

For all intents and purposes, though, a Portuguese man-o’-war—so labeled for its resemblance to an 18th-century warship—may as well be a jellyfish, given the bell-like float or bladder and the long draping polyps and tentacles, which may be dozens of feet long.

That vividly blueish or purplish bladder floats on the sea surface, helping propel the man-o’-war by ocean current or wind.

While not a true jellyfish, the Portuguese man-o’-war has tentacles similarly armed with nematocysts, and its sting can be quite painful.

Jellyfish Season at Tybee Island

We’ve already sketched out the rough basics of jellyfish seasonality off Tybee Island in our individual species profiles.

Some jellies, such as the lion’s mane and the mushroom cap, are more common in winter; others, such as the sea wasp, the moon jelly, and the sea/bay nettles, tend to be evident mainly in the summer months.

Still other jellyfish, such as the cannonball, are essentially year-round denizens of North Georgia’s coastal waters.

That said, jellyfish season at Tybee Island can essentially be equated with the summer and early fall months, on account those are the time of year when the vast majority of people, locals and visitors alike, tend to be in the water and thus most exposed to jellyfish risk.

And those months also describe when the more heavy-hitting sea jellies, namely sea wasps and the sea and bay nettles, are most likely to be encountered.

Most jellyfish stings along the U.S. East Coast are attributed to sea and bay nettles, though the most serious injuries in Tybee waters likely stem from run-ins with sea wasps (with some occasional severe stings resulting from the less-common Portuguese man-o’-war).

Jellyfish stings are pretty frequent in the warm season at Tybee Island.

A 2020 Savannah Morning News article suggested that Tybee Ocean Rescue receives reports of anywhere from 100 to 200 jellyfish stings a day during this timeframe.

But almost all of these are decidedly minor, translating to nothing more than a brief burning sensation.

Only a handful cause more severe welts or rashes, let alone intense reactions requiring major medical attention.

Keep in mind that, even if you don’t actually get into the water at Tybee Island, you may run into jellyfish.

It’s not uncommon for sunbathers and beachcombers to see dead or dying sea jellies washed up on the beach, particularly with prolonged onshore breezes and currents or strong high tides.

In May of 2021, for example, Tybee Island made headlines thanks to thousands of washed-ashore cannonball jellies on its northern beaches.

Local lifeguards will often bury or remove beached jellyfish, but nonetheless you should be aware of the potential for encountering them.

Avoiding & Treating Jellyfish Stings at Tybee Island (Tips & Things to Know)

You can take many measures to minimize the chance you’ll get stung by a jellyfish at Tybee Island—even while resting assured that a sting is unlikely to result in a serious medical issue, unless you’re allergic or very unlucky.

Purple warning flags posted at Tybee Island beaches suggest the presence of dangerous marine life, which often reflects large numbers of jellyfish in nearshore waters.

Steer clear of the water if those purple flags are flying.

Also be wary of the potential for significant jellyfish numbers if a beach is strewn with washed-up jellies—that may well go without saying. If you see a lot of floating debris in the waters off the beach, you might also assume that currents or wind have driven jellyfish close to the beachfront as well.

Strong onshore currents or breezes in general warrant a bit of caution if you’re taking to the water, given the greater likelihood of running into drifting jellies.

Speaking of beached jellyfish, avoid touching them!

Jellies—including dead ones—can still deliver a sting hours, days, even weeks after washing ashore.

(Keep a close eye on young children when steering your way down a jellyfish-strewn beach, in case they can’t resist prodding those globby masses with fingertips or bare toes.)

While understandably not everybody will follow this precautionary measure, wearing a wetsuit with booties can protect you to some extent from jellyfish stings.

Clothing in general can buffer you from the stinging cells, but it’s not complete immunity by any means.

If you or somebody in your swimming or beachgoing party does get stung, watch for worrisome signs such as shortness of breath, chest pains, or severe dermatological response.

If these develop, call 911 or the National Poison Help Hotline (toll-free at 1-800-222-1222).

Somebody who has an allergic reaction to a jellyfish sting may be treated with epinephrine or an oral antihistamine.

If tentacles are still attached to the victim, remove with tweezers. Don’t scrape them off, which can spread and aggravate the stinging cells.

Household vinegar is a widespread and often very effective treatment for jellyfish stings.

Rinse it over the sting area for 30 or more seconds. Afterward, soaking the sting site in hot water may ameliorate the irritation as well, as can pain-relief ointments such as hydrocortisone cream.

Lifeguards at Tybee Island beaches commonly provide aid to swimmers or surfers who’ve been stung by jellyfish.

They typically have a vinegar solution on hand for just these situations. They also sometimes apply the same kind of “hot pack” they use to treat stingray injuries if the jellyfish sting is more severe.

There is a 24-hour urgent-care center on Tybee Island (602 1st Street, Suite A), and hospitals are close by in the Savannah metro area.

Wrapping Up

You may or may not run into jellyfish on your visit to Tybee Island.

Sure, you might see one drifting by in the nearshore shallows, or even whole rafts of them stranded on the beach.

Just as likely, you’ll blissfully stroll and swim along these beloved seashores without noticing these common and important invertebrates, which all things considered are inoffensive critters floating their way passively along on the sea currents.

Good as it is to be aware of their presence, you don’t need to regard Tybee’s native sea jellies with dread by any means.

For more, don’t miss:

Hope this helps!