The dozens of islands composing the Whitsunday archipelago off the Queensland coast make it one of the prime destinations for locals and tourists alike in the central Great Barrier Reef. Boating, paddleboarding, swimming, snorkeling, and scuba diving are some of the go-to ways to enjoy this scenic chain and the astonishing coral realm so near at hand.

If you’re planning on enjoying the water here, however, you might be wondering:

Do the Whitsunday Islands in Australia have jellyfish? How common are jellyfish stings in the Whitsundays?

The tropical waters of the Whitsundays support a variety of jellyfish, including those—locally known as “stingers”—which can cause painful and even life-threatening stings. Numerous species, however, are essentially harmless to people.

Some of the jellyfish that inhabit the Whitsunday Islands are:

- The Australian box jellyfish or sea wasp

- The Irukandji jellyfish

- Purple stingers

- Jelly blubbers

- White-spotted jellyfish

- Moon jellies

- Lion’s mane jellies

- And upside-down jellyfish

It’s important to take “stinger safety” seriously while vacationing in the Whitsundays, however jellyfish stings here are relatively rare due to clear markings of safe water, stinger nets, and other preventative measures.

Let’s take a look at some of the most notable kinds of Whitsunday Islands jellyfish, then talk about ways to stay safe when enjoying their habitat!

Types of Whitsunday Islands Jellyfish

A variety of sea jellies might be encountered in the waters of the Whitsundays.

The following are just some of the more common and/or notable ones. And speaking of notable, we’ll begin with the two most infamous of the local “marine stingers.”

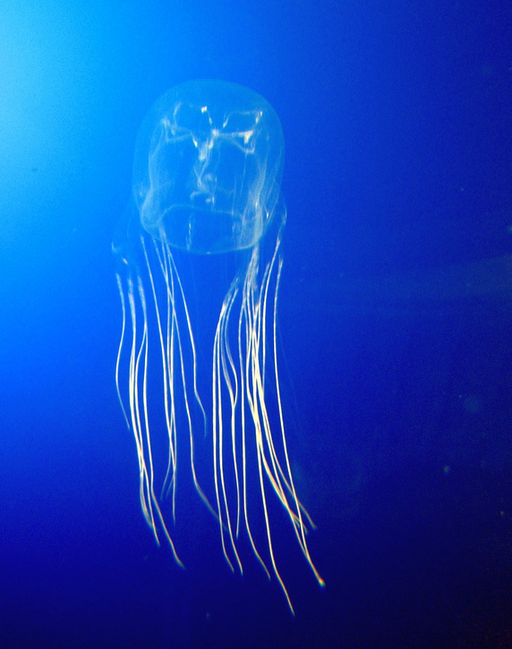

The Australian Box Jellyfish or Sea Wasp (Chironex fleckeri)

This is arguably the most all-around notorious jellyfish in the world.

The Australian box jellyfish or sea wasp is the biggest of all the cubozoans, or box jellies, which belong to a separate taxonomic class than the “true” jellyfish, or scyphozoans.

Box jellies are so-called for their squared-off bell, which typically sports clusters of tentacles at the four corners. The sea wasp’s bell may be a foot or so in diameter and sport upwards of 60 tentacles that may be 10 feet long.

This is a striking—and intimidating—creature indeed.

Especially common in coastal and estuarine waters in summer, sea wasps can pack a heck of a wallop with their stinging cells.

The tentacles leave angry marks that look like whiplashes, with intense burning pain an immediate consequence of a run-in.

Serious stings may cause cardiac arrest or death, which is more common among children, given their small body size, and when the box jelly in question is a large one.

The Irukandji Jellyfish (Multiple species, but most notably Carukia barnesi)

Numerous species belong to the group of Irukandji jellyfish, but off the Queensland coast that common name typically refers to Carukia barnesi.

This is also a box jellyfish, but dramatically smaller than the sea wasp; the bell is often only roughly fingernail-sized.

The tiny dimensions and semi-transparent tissue of the Irukandji jellyfish makes it very hard to spot in the water. That explains why stings are fairly common in this region.

The sting of an Irukandji jellyfish is significantly less painful than that of a sea wasp; indeed, it’s often downright mild. But after a half-hour or so, some people who’ve been stung (definitely not all) may come down with symptoms of Irukandji Syndrome.

These may range from a sick-feeling stomach to intense muscle cramps, headaches, chest pain, and pronounced anxiousness. In rare cases, Irukandji Syndrome can lead to death, so it’s definitely something to be aware of.

The Purple Stinger (Pelagia noctiluca)

The beautiful purple stinger can cause a painful sting, hence its nickname of “purple people eater.”

Unlike the local box jellies, though, the purple stinger’s sting—which may come associated with an itchy rash—is not normally dangerous, just decidedly unpleasant.

The purple stinger displays a lovely purplish or mauve color (it’s also called the mauve stinger) and trails four mouth arms and eight tentacles from its bell.

Interestingly, stinging cells in this species aren’t restricted to the mouth arms or tentacles, but actually cover the bell as well.

The Jelly Blubber (Catostylus mosaicus)

According to the Australian Museum, you’re more likely to encounter the wonderfully named jelly blubber in coastal Australian waters than any other sea jelly. It’s a handsome creature, too, popular in aquarium displays.

The bell of the jelly blubber gets its blueish hue from symbiotic algae. It has no mouth, but takes in prey through openings in its tentacles.

You might not enjoy a sting from the jelly blubber, but it’s not dangerous.

Large aggregations or “swarms” of jelly blubbers sometimes materialize in bays, inlets, and river mouths.

The White-Spotted Jellyfish (Phyllorhiza punctata)

The white-spotted jellyfish is another gorgeous animal, named for the dense white spots that mark both its bell and the tips of its tentacles.

It’s a good-sized jellyfish, with a bell that may be 20 inches across.

White-spotted jellies aren’t dangerous to people, given their mild or essentially nonexistent sting.

They’re native here in the waters off Australia’s eastern coast, but notorious as an exotic invasive species in such farflung places as the Caribbean.

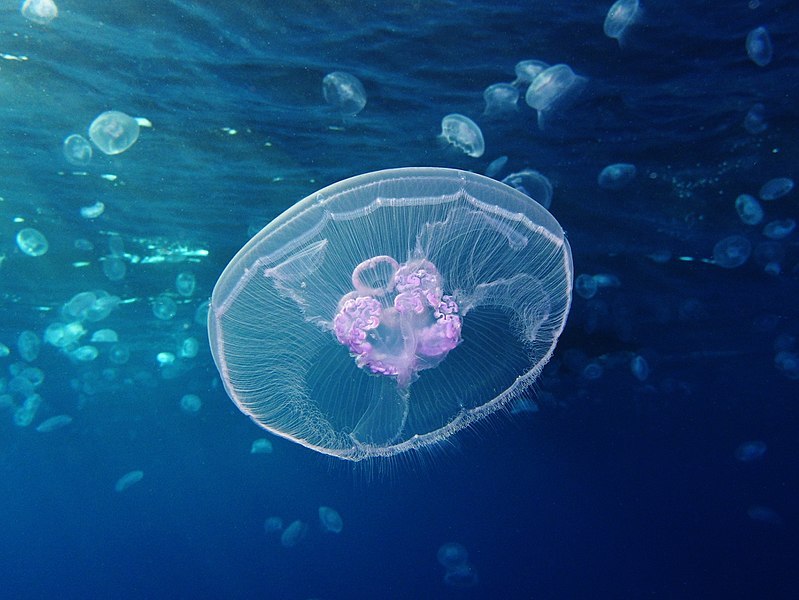

The Moon Jelly (Aurelia aurita)

The common and extremely widespread moon jelly has a dish-shaped, see-through bell with four horseshoe-shaped glands that make it unmistakable.

The dense tentacles ringing the bell are fine and very stubby, and thus hard to see.

Moon jellies, which may also appear in swarms, have an extremely mild sting, and indeed many people wouldn’t notice any reaction brushing against one.

The Lion’s Mane Jellyfish (Cyanea capillata)

One could make an argument for the lion’s mane being the world’s most spectacular jellyfish.

It’s certainly the biggest, with specimens from temperate and polar waters sometimes growing a bell six feet or more across and dangling dense clustered tentacles 100 or more feet long.

While lion’s mane jellies are found off the Queensland coast, including along the Great Barrier Reef, this and other tropical populations don’t seem to produce individuals of anywhere near such a large size.

The lion’s mane jellyfish can deliver a potent sting, but it’s not usually life-threatening.

The Upside-Down Jellyfish (Cassiopea)

Upside-down jellies are named for their typical stance on the seafloor, with bell down and chunky tentacles poised upright.

That position gives the dinoflagellates that live symbiotically within Cassiopea plenty of sunlight to power photosynthesis, which thereby supplies much of the jellyfish’s sustenance.

Upside-down jellyfish don’t pose any real threat, but recent research shows that the globs of venomous cells they release in their vicinity likely explains the mild irritation people swimming in their vicinity can experience—the effect of so-called “stinging water.”

(Want to learn about sharks in the Whitsundays? Click here.)

Whitsunday Islands Jellyfish Season & Calendar Explained

You’ll often hear about a “stinger season” off the Queensland coast (including the Whitsunday Islands) running between about November and May.

November through May are indeed the prime months for the most serious jellyfish stings, those of the sea wasp and the Irukandji jellyfish.

But experts are rightly leery about referring to a specific season when it comes to potentially dangerous jellyfish, because stings can and do happen outside those months.

Avoiding & Treating Jellyfish Stings in the Whitsundays

Despite their reputation, serious stings from box jellies in the Whitsunday Islands and elsewhere along the Queensland coast are relatively rare.

One reason why Australia is so associated with these marine stingers is because the country leads the world in research on them and the pathology of their stings.

This focus can sometimes lead tourists to mistakenly believe the Land Down Under is unusually plagued by lethal box jellies.

Actually, Australia sees far fewer fatalities from box jellies than some other parts of the Indo-Pacific, notably the Philippines. That seems to partly stem from the well-established educational and preventive measures Australia has taken with regard to marine stingers.

“Stinger nets” help protect many popular beaches in the region from box jellies, with flags demarking safe places to swim.

And you can greatly reduce your vulnerability to a serious sting from a sea wasp or an Irukandji jellyfish by wearing a full-body “stinger suit.” Such a neoprene or Lycra suit not only buffers most of your body from jellyfish stings, but also protects you from the sun!

Although Irukandji jellyfish are very hard to see, there are numerous clues to their potential presence that can help you avoid the water when they might be around.

These include easily detected sea lice or salps—prized jellyfish prey—in the water, or sustained northeasterly winds that may drive jellies inshore.

If you are stung, don’t panic. Stings from many jellyfish, as we’ve already discussed, may be painful or irritating, but don’t result in long-term damage or risk of death.

Keep an eye out for signs of an allergic reaction, though, which in some people may be prompted even by a “harmless” jellyfish’s sting.

The welts left behind by a sea wasp—not to mention the likely screams of pain a victim will immediately issue—should be enough to diagnose a sting from that box jelly.

Use gloves or other protective layers to remove any tentacles that might be left behind around the sting, and apply liberal amounts of vinegar—a good remedy for any jellyfish sting, as it deactivates the stinging cells.

It’s for that reason—and especially to provide immediate treatment for sea-wasp or Irukandji stings—that area lifeguards typically have vinegar at the ready on well-used beaches.

But it’s also a good idea to carry vinegar yourself, especially if you’re visiting unpatrolled or more remote beachfronts or bareboating your way through the Whitsundays.

Seek immediate medical attention if a jellyfish victim is exhibiting signs of cardiac arrest, respiratory problems, or Irukandji Syndrome.

Wrapping Up

Jellyfish are a fact of life in the Whitsundays and throughout the Great Barrier Reef, playing their own important role in this globally outstanding marine ecosystem.

Heed any current advisories regarding marine stingers, swim at patrolled and net-protected beaches whenever possible, wear a stinger suit, and tote vinegar while enjoying the islands and the adjoining mainland, and you’ll have a good chance of avoiding any problems with these remarkable and ancient invertebrates!

For more guides, check out:

Hope this helps!