At the doorstep of the central section of the Great Barrier Reef—the planet’s largest (and most famous) coral reef—the Whitsunday Islands off the Queensland coast make a beloved getaway for Australians and international tourists alike.

From guided dives and snorkeling to self-guided yachting tours (“bareboating”), the Whitsundays see a lot of folks getting on and into the water.

Particularly given a string of incidents in 2018 and 2019—and controversy over control measures (baited drumlines) being taken in the name of protecting water users—the islands have also gained something of a reputation for sharks.

So let’s dive in: Do the Whitsunday Islands in Australia have sharks? Is it safe to swim and surf in the Whitsundays? How common are shark attacks at the Whitsunday Islands?

Queensland’s Whitsundays and the adjoining Great Barrier Reef are home to a rich and diverse group of sharks. Among the most common/frequently seen are:

- Grey Reef Sharks

- Whitetip Reef Sharks

- Blacktip Reef Sharks

- Silvertip Sharks

- Scalloped Hammerheads

- Sicklefin Lemon Sharks

- Tawny Nurse Sharks

- Zebra Sharks

Shark attacks in the Whitsunday Islands are rare but not unheard of, usually occurring to the tune of 1-3 unprovoked attacks per year, usually non-fatal. Common sense safety measures are recommended here for swimmers, surfers, and fishers.

But let’s get the main take-home message out there right off the bat: As everywhere in the World Ocean—and like just about any other large animal—sharks pose a potential hazard to humans, but on the whole pose very little danger compared to other hazards (not least drowning).

Having suffered mightily from an undeserved reputation for bloodthirstiness, sharks—essential top-level predators that help regulate the marine ecosystem—ought to be viewed with respect and wonder, not uncontrolled fear.

Let’s take a closer look at the types of sharks that live near the Whitsunday Islands, photos, shark attack history and statistics, and more.

Types of Whitsunday Islands Sharks

The following list isn’t completely exhaustive, as an impressively large roster of sharks could conceivably drift through the Whitsundays given their geography and the astounding biodiversity of the Great Barrier Reef.

But it does cover most of the species likeliest to be seen around the archipelago and the adjoining reaches of the mighty reef.

Grey Reef Shark

The sleek grey reef shark may be the most abundant shark on the Great Barrier Reef.

Exhibiting the classic look of a “typical” shark in Family Carcharhinidae—the requiem sharks—the grey reef shark can be distinguished from close relatives by the conspicuous black edge to the entire trailing edge of the tail (caudal) fin.

Reaching lengths of six to eight feet, grey reef sharks often patrol reef drop-offs, seeking bony fish as well as octopus, squid, lobsters, and other varied prey.

When threatened—say, by an over-inquisitive diver—this species may perform a warning display and, if still pressed, bite out of self-defense.

Whitetip Reef Shark

Another very common resident of the Great Barrier Reef, the whitetip reef shark is a slimmer creature compared to the grey reef shark, and easily distinguished by its blunt snout and white-tipped first dorsal and upper tail fins. It grows to about four to six feet long.

Unlike many of its relatives, whitetip reef sharks don’t have to swim to breathe, so they’re often seen resting motionless on the seafloor or in caves during the day.

At night, they’re active hunters of small critters such as crabs and mollusks, adeptly snaking into reef nooks and crannies when hunting.

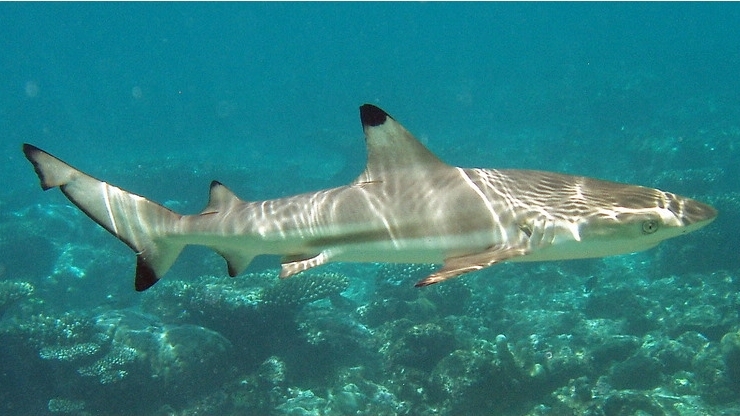

Blacktip Reef Shark

Like the grey reef and whitetip reef sharks, the blacktip reef shark is a common sight over coral complexes in the tropical Indo-Pacific.

It can be identified by its stubby snout and the characteristic black tips on all of its fins.

Usually five feet or less in length, blacktip reef sharks often hunt over reef flats and in lagoons, seeking small fish, crustaceans, squid, and even the occasional seasnake.

Silvertip Shark

The silvertip shark is notably bigger than the requiem sharks we’ve covered thus far, capable of exceeding 10 feet in length and weighing several hundred pounds.

It gets its name from the white tips and trailing edges of all its fins. The long pectoral fins of the silvertip are also distinctive.

Silvertip sharks may be encountered along the edges of reefs and the continental shelf, coursing after bony fish, rays, smaller sharks, and cephalopods.

They’re a notably bold species and this disposition, coupled with their decent size, warrants basic caution when sharing the water with them.

Silky Shark

Another good-sized requiem shark that might be encountered along drop-offs in the vicinity of the Whitsundays is the silky shark, locally known as the grey whaler.

Reaching around 10 feet long, the silky—displaying the typical carcharhinid form—gets its common name from its smooth-looking skin.

Feeding mainly on bony fish and cephalopods, silky sharks in parts of their range have earned the nickname of “net-eating shark” due to their habit of raiding seine nets.

Bronze Whaler

The bronze whaler, also called the copper shark, is another requiem species that, while more common in temperate and subtropical waters, is known to occasionally frequent the vicinity of the Whitsundays.

It boasts a nice set of distinctively hook-shaped teeth, and reaches 11 or so feet at maximum.

Tiger Shark

The largest requiem shark on the Great Barrier Reef—and, indeed, in the world—is the tiger shark. It’s a hard species to mistake for another, given the heavy-set head with its wide jaws and blunt snout, the relatively short pectorals and first dorsal fin, and a body defined by a whitish belly and a black- to gray-brown black patterned with namesake stripes that grow fainter with age.

Tiger sharks commonly grow to 10 to 14 feet long, with the biggest specimens approaching 20 feet long; such giants may weigh more than a ton.

Armed with those powerful chompers and robust serrated teeth, tiger sharks are top predators that will famously munch on just about anything, from lobsters and crabs to sea turtles, dolphins, seabirds, and sundry free-floating detritus.

Tiger sharks enthusiastically scavenge whale carcasses, which in parts of tropical Australia have drawn both tiger sharks and saltwater crocodiles at the same time.

(Crocodile remains, incidentally, are among the incredibly varied items that have been found in tiger-shark stomachs.)

Bull Shark

The two most formidable requiem sharks are the tiger and the bull shark.

While smaller than the former, the bull shark is nonetheless a very impressively proportioned animal: Females as large as 13 feet have been recorded, and even a bull shark of more typical length—say, eight or 10 feet long—is still a notably thick-bodied and powerful-looking beast, with heavy jaws and dentition.

Known for their tolerance of freshwater, bull sharks utilize a variety of coastal habitats.

While not a super-common sight in the Whitsundays, the islands certainly fall within their range.

A large female bull shark was tagged in Cid Harbour in January 2020 and tracked throughout that year as she ranged from the far north of the Great Barrier Reef down to the Sunshine Coast.

Sicklefin Lemon Shark

The sicklefin lemon shark is a common reef-, lagoon-, and mangrove-dweller in the Whitsunday Islands vicinity.

With its light hide, somewhat squat body plan, and equal-sized dorsal fins, it much resembles its close cousin the lemon shark of the Americas, but has more sharpy curved pectorals (hence “sicklefin”).

Reaching lengths of 11 feet or more, sicklefin lemon sharks feed on a wide variety of bony fish and elasmobranches (sharks and rays) as well as crustaceans, mollusks, and seabirds.

Oceanic Whitetip Shark

A rare sight in the Whitsundays, oceanic whitetip sharks nonetheless ranked among the most common pelagic sharks in the world until recently; stocks worldwide have plunged dramatically due to overfishing and bycatch, a worrisome trend indeed.

On Australia’s east coast, the increasingly rare oceanic whitetip ranges as far south as the Sydney area.

The oceanic whitetip is among the more distinctive-looking requiem sharks, unmistakable with its huge rounded pectoral fins and the white tips of the pectorals and dorsal fin.

This sturdy shark—which often dominates other species at whale carcasses and other feeding aggregations—may reach 11 to 13 feet.

Scalloped Hammerhead

The vast global tropical and warm-temperate range of the scalloped hammerhead definitely encompasses the Great Barrier Reef and the Whitsundays.

This is a medium-sized hammerhead, reaching about 11 feet in maximum length. It’s distinguished by a central notch as well as side indents on the curving front of its T-shaped head.

Known for schooling migrations, scalloped hammerheads are mainly a coastal pelagic predator that feeds on rays, smaller sharks, and bony fish.

Great Hammerhead

The aptly named great hammerhead is the biggest of the world’s hammerhead sharks, with large individuals reaching and perhaps exceeding 20 feet long.

It has a more squared-off front to its head than the smaller scalloped hammerhead.

An occasional (and always-magnificent) sight on the Great Barrier Reef, the great hammerhead is an apex predator with a particular fondness for stingrays.

Tawny Nurse Shark

Another of the most common sharks in the Whitsundays, the tawny nurse shark is a long-tailed bottom-dweller that may reach 10 or so feet long.

It may appear sluggish when resting on the seabed or slowly cruising, but it’s an active nighttime reef hunter that sucks small fish, crustaceans, and other prey out of crevices and also one of the Queensland coast’s prized, hard-fighting gamefish.

Zebra Shark

Like the tawny nurse shark, the zebra shark is part of the carpetshark order, whose members tend to have small mouths often flanked by barbels.

This reef-haunting species is easily one of the most spectacular-looking in the Whitsundays: Its bulky, ridged, and long-tailed body comes festooned with spots as an adult, while juveniles also incorporate the stripes that give this shark its common name.

(Heads up: The zebra shark is commonly called “leopard shark” in Australia—really, perhaps the more accurate label, given the adults’ spots—but shouldn’t be confused with the unrelated coastal shark of that name found along the Pacific coast of North America.)

Wobbegongs

The multiple species of wobbegong shark found on the Great Barrier Reef, in the same order as nurse and zebra sharks, give away where the “carpetshark” name comes from:

Flattened and ornately patterned, these ambush hunters do indeed resemble a beautiful rug. This camouflages them as they lie in wait on the seabed, explosively launching upwards to snatch passing fish.

Most are in the vicinity of four or five feet long, but some species—including the spotted and Gulf wobbegong found in these waters—may exceed nine feet long.

Epaulette Shark

Yet another carpetshark—and yet another real dazzler—the epaulette shark is a little reef-dweller named for the resemblance of the large black spots on its front sides to the shoulder decorations commonly found in military uniforms.

The Great Barrier Reef is a center of abundance of the epaulette shark, known from both Australian and New Guinean coastal waters.

Whale Shark

Remarkably, the enormous, pelagic whale shark—biggest of all fish, and the biggest vertebrate outside of the great whales themselves—belongs to the same carpetshark order including so many pintsized, sedentary reef-dwellers.

Whale sharks can reach at least 60 feet in length, and they combine that gargantuan size with a striking look: a front-heavy, humped profile, an incredibly wide but narrow mouth, a grand tail with equal-sized caudal lobes, and a gorgeous ridged and spotted hide.

Mainly feeding on plankton as well as small fish, whale sharks are known to gather in large feeding aggregations in certain parts of the world, including Western Australia’s Ningaloo Reef.

Such gatherings haven’t been documented as of yet in the Great Barrier Reef, but whale sharks are fairly regularly seen in this region in summer months.

Scientists are working to learn more about what significance this vast coral garden may hold for the heftiest of all fish.

(Worried about jellyfish in the Whitsunday Islands? Click here to read.)

Shark Attack History & Statistics in the Whitsunday Islands

Shark attacks are few and far between in the Whitsunday Islands.

You’ve got a much greater chance of drowning, getting stung by a jellyfish, or being injured or killed in a traffic accident en route to your boat than being mauled by a shark.

Of the species we listed above, the most potentially dangerous—based on size and temperament, and in certain cases confirmed recorded unprovoked attacks on people on a global basis—would likely include the tiger, bull, oceanic whitetip, bronze whaler, silvertip, and great hammerhead.

The records of the Shark Research Institute’s Shark Attack File (as tabulated here, going back to the 1800s!) show just a handful of unprovoked attacks per year, usually non-fatal.

In the 90s: A spearfisherman bitten on Lime Reef in 1993, a snorkeler off Whitehaven Beach in 1997, and a scuba diver Whitsunday Passage, also in ‘97.

That last attack was attributed to a smallish to medium-sized tiger shark.

Some rather serious—although still paltry-in-number—shark attacks have occured in the Whitsundays in the 21st century.

In 2010, a 60-year-old snorkeler received a significant sharkbite at Dent Island. But it was in 2018 and 2019 that the archipelago really made headlines for the predatory fish.

Three attacks took place in the popular Whitsunday bay of Cid Harbour in the second half of 2018, two occurring within 24 hours of one another in September.

The first of those saw a 46-year-old Tasmanian tourist severely wounded on the thigh. This was followed up by a bite on a 12-year-old girl. Both of these were non-fatal.

The species of shark responsible were not determined, though an article on the attacks in The Inertiaquoted Dr. Mark Read, the Great Barrier Reef Marine Park Authoritty’s assistant director of reef conservation, as speculating that a bull shark or bronze whaler—or possibly a tiger shark—were likely suspects.

In November of that year, a 33-year-old man was killed by a shark in Cid Harbour. He’d been on a yachting cruise with a group, and had gotten into the water to let a friend take a turn on a stand-up paddleboard when he was attacked.

In October 2019, meanwhile, two men on a day cruise were attacked by a shark in Hook Passage near Airlie Beach (a mainland departure hub for Whitsunday excursions): one losing a foot, the other receiving a “serious laceration” on his leg.

Wrapping Up

Don’t let an irrational fear of sharks ruin your visit to Queensland’s Whitsunday Islands—or inspire negative feelings toward these magnificent underwater predators.

But do follow basic shark safety protocols: Avoid swimming alone or at dusk, follow posted signs and instructions from lifeguards or other officials, and don’t wear shiny jewelry in the water.

Nine times out of 10, a sighting of a shark while paddling, boating, or snorkeling in the Whitsundays is likely to be an unforgettably amazing, even inspiring, experience!

For more, check out:

Hope this helps!